Greetings from BSG Chairperson Mr. Vishesh Gupta

Dear Readers,

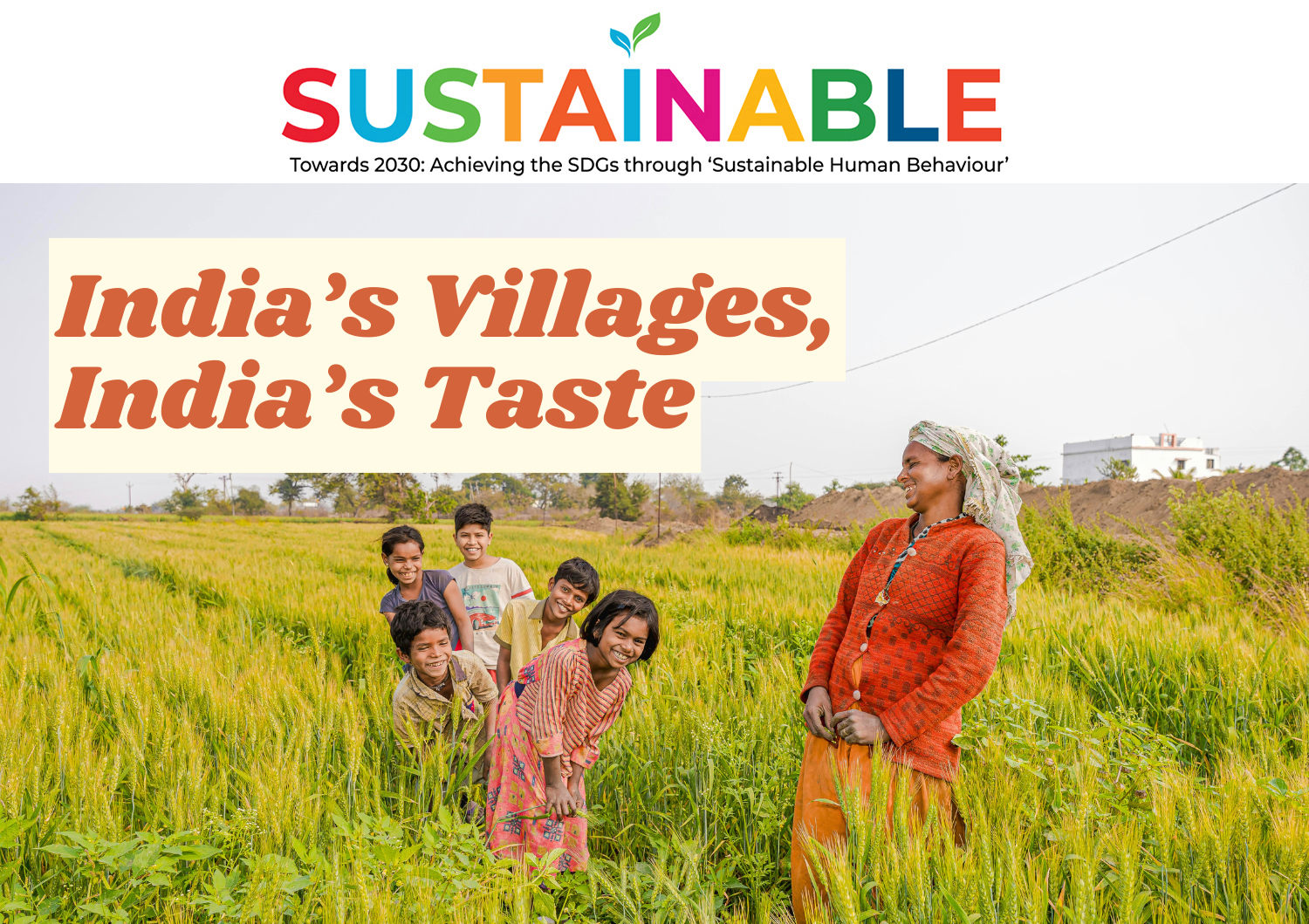

In cities growing hotter each year, the monsoon arrives like a long-awaited guest. Its first drops hush the heat and bring momentary relief to lives lived in concrete. But beyond the city’s edge, in rural India, rain is not just welcome. It is essential. Clouds are coaxed, like loved ones, to return home. Folk songs burst forth as prayer. Plea to the clouds. Praise for the soil. Hopes whispered in rhythm.

And while there are songs for the rain, there are songs for its absence too. Many poets and folk singers have written of the chappaniya akal – the devastating drought of 1899 in Rajasthan. In local memory, it lives on through verses like:

Oh mharo chappaniyo kaal

Fero mat aj bholi duniya mein

Bajre ri roti gawar kee fali

Mil jaye toh wah hi bhali (Mongabay 2022)

[Oh my drought. Now do not come to the land of innocent people, because even a simple meal of millet rotis and cluster beans becomes a luxury.]

These aren’t merely seasonal rituals. They are reflections of how deeply farmers live in conversation with nature, how rain, soil, and seed are their sacred companions. Across generations, it is these songs and traditional wisdom that have passed down knowledge, comforted drought-worn hearts, and tethered people to land.

This is the spirit of rural India. Where climate is not simply endured; it is sung to. Where agriculture is not simply labour; it is legacy. In the countryside, nature is not a resource. It is family.

Rural India shapes many aspects of the nation. But it is in the farms, where most hands still labour, that the first chapters of our food are written. And so, we begin there.

As we mark World Food Safety Day and the World Day for Rural Development in this Issue, we’re reminded that nourishment isn’t born in the city. It travels to it. This intimate world of farming – so ancient, so alive – is under threat. Farmers face growing climate extremes, shrinking incomes, and an ever-widening distance from the plates they fill. They are asked to feed the nation, even as they struggle to feed their own families.

This edition of the ‘Sustainable’ newsletter is an urgent call for us to recognize that what sustains us is not only grown, it is sung, shared, and sacrificed for.

Sustainability is not a product we will one day arrive at. True sustainability lies in the relationships we nurture – with nature and with one another. Let us truly value how deeply we are interconnected – and ask, with sincerity:

How can we participate more meaningfully in this chain, to honour it and help it thrive?

Warm Regards

Vishesh Gupta

Chairperson, Bharat Soka Gakkai

Rural India is home to over 65% of our population. A 2023 Statista report shows that 59% of India’s rural workforce is employed in agriculture, compared to just 6.7% in urban areas. Rural India is where our food takes root. But despite its importance, it is often overlooked in conversations about sustainability and progress.

Around 42.3% of India’s workforce is engaged in agriculture. Yet farming contributes just 18% to our GDP. This massive imbalance isn’t just an economic figure. It reflects the deep undervaluing of those who grow our food. And while cities expand and diets diversify, the real work of nourishment – of soil, seed, and sustenance-still happens in the villages.

For decades, farming in India has been increasingly reliant on chemicals, inputs, and greater strain. This has come at a high cost: soil degradation, water scarcity, declining biodiversity, and debt-driven distress. Over 89% of Indian farmers own less than two hectares of land. More than 50% of farming households are in debt. Extreme heat and erratic rainfall, made worse by climate change, have led to declining yields and greater instability. Traditional seed varieties have been replaced by water and chemical-intensive crops, leaving farmers vulnerable and trapped in cycles of dependency.

This is not just a rural issue. Rural and urban lives are more connected than we realise. We feel the ripple effects in urban life: soaring food prices, compromised nutrition, and insecure supply chains.

In this context, regenerative farming is emerging as a practical and hopeful solution.

Regenerative practices aim to restore soil health, reduce chemical inputs, and make farming more resilient to climate extremes. In Andhra Pradesh, Community-Managed Natural Farming (CMNF) is a model that uses local resources like cow dung and plant extracts, avoids all synthetic chemicals, and treats the farm as a living ecosystem. Formed by the Department of Agriculture, Government of Andhra Pradesh, this model covers 6 million farmers in 13 out of 26 districts in the state.

Did You Know?

- Over two-thirds of India’s milk supply comes from rural households.

- The cotton in your clothes likely started in a field in Maharashtra, Gujarat, or Telangana – picked and sorted by rural hands.

- Over 90% of workers in India are informal and out of these, those engaged in rural areas are significantly more than those of urban areas

- Countless urban festivals, from Diwali to Sankranti, are made possible by rural harvest cycles and labour.

- Crafts from rural India, like Madhubani, Chikankari, or Bastar ironwork, sustain families and carry centuries of heritage into our homes.

- Rural forests and wetlands, many protected and stewarded by local communities, are among India’s biggest carbon sinks.

The results speak for themselves:

- 44% lower input costs

- 7–26% higher crop yields

- 49% higher net incomes

- Richer soil, more pollinators, better water retention

This shift was initiated by farmers themselves, especially women, through a social movement called “Zero Budget Natural Farming”. In other parts of India, similar efforts are taking root. In Odisha, tribal communities are conserving traditional seed varieties. In Himachal, farmers are switching to climate-resilient millets and pulses. These are not isolated experiments. They are part of a larger movement to reimagine farming as a practice that works with nature, not against it.

What Can You Do?

- Support rural producers through farmer collectives, cooperatives, and platforms that link you directly to the source.

- Learn about regenerative farming and amplify stories of rural innovation, not just urban tech.

- Buy seasonal and local. Even small shifts in food habits reduce pressure on long-distance rural supply chains.

- Engage with policy, however small your influence: support initiatives that protect small farmers, promote seed diversity, and invest in agroecology.

- Build emotional connection: read rural stories, follow grassroots leaders, remember that sustainability is more than a product, it’s a relationship.

But these methods, as hopeful as they seem, aren’t a miracle fix. They still need protection, recognition, and long-term support. Most of the farmers embracing this path still face major barriers – lack of access to formal credit, unreliable markets for naturally grown produce, little protection from climate shocks, and minimal recognition in national policy frameworks. Many are locked out of mainstream subsidy systems that favour chemical-based agriculture. Others struggle with social pressure or a lack of technical training.

If this transformation is to endure, it cannot remain confined to pockets of experimentation. It must become a national ethic, championed by policy, supported by cities, and sustained by communities.

Whether this movement thrives or fades depends, in part, on whether we in cities choose to see rural India not as disconnected relics of the past, but as a partner in shaping what comes next.

Carbon Farming

What it means:

A set of agricultural and land-use practices designed to remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and store it in soil and plants. This helps slow climate change while boosting farm productivity.

Why it matters:

- Increases soil organic matter, improving fertility, water retention, and drought resilience

- Promotes climate-smart agriculture by turning farms into living carbon sinks.

- Supports SDGs 2, 13, and 15 through healthier soils, climate action, and sustainable land use.

How does it work?

Plants absorb CO₂ from the air during photosynthesis; that’s how they grow. But here’s the key part: When we use farming methods like adding cover crops, applying compost or biochar, and reducing tillage, more carbon gets trapped in the roots and soil. Instead of releasing CO₂ into the air (which worsens global warming), we’re storing it safely in the ground.

Farmers in India, especially small and marginal, are starting to use these methods. ISRO has now partnered with Rajendra Prasad Central Agricultural University (RPCAU), Pusa, to promote carbon farming in Bihar!

Source: Carbon Cycle Institute

To Read

To Read

Climate Resilience Takes Root on India’s Mint Farms

India is the world’s top producer and exporter of mint oil, but climate change, rising costs, and shifting global trade are putting pressure on farmers and disrupting the supply chain. Find out how farmers are coping.

How Nagaland’s Ancient Farming Methods Turn Floods into Food

The Zabo farming system, practiced in Kikruma village of Nagaland, is a brilliant indigenous method that combines sustainable agriculture with effective flood control.

Celebrating India’s Rural Women: 3 Inspiring Stories of Women Farmers Bringing About Change

A growing number of women in India’s rural regions are stepping into farming roles traditionally held by men, not only caring for their families but also managing fields, livestock, and market sales.

6 Sustainable Practices from Rural India the World Can Learn From

These sustainable practices serve as simple, effective lessons in low-impact living and offer valuable insights for city dwellers

To See

To See

To Turn a Tide

Learn how ‘agri-tech’ is emerging to provide simple solutions to farming problems.

Armed with microfinance loans, rural women in Kolkata are kickstarting fruit nurseries

This insightful episode of Eco India highlights how microfinance loans are uplifting rural women in the outskirts of Kolkata.

How Regenerative Agriculture is Helping Small Farmers Grow and Earn Better in Urban Hubs

A compelling tale of rural innovation. Learn how regenerative practices restore the soil and boost the income of farmers.

To Listen

To Listen

Why Nutrient Density is the Future of Farming

An enlightening podcast for anyone curious about soil health and food quality connections.

How Rural Entrepreneurs Could Help India Create 1 Million Jobs

This engaging conversation delves into how many farming cooperatives and small-scale ventures are being empowered to develop sustainable livelihoods.

To Play

To Play

Nutrients for Life

Step into the shoes of a farmer and provide corn crops with the nutrients they need to grow.

There are lives that are human, animal, and elemental that shape our days in ways we rarely notice. The hands that harvest our food. The trees that purify the air. The rivers that cradle entire civilizations. The microbes that till the soil. The bees that pollinate our orchards. These are not just background details. They are the lifeblood of our existence.

But in the noise of modern life, we forget. And in forgetting, we narrow our circle of care.

“Certainly, global citizenship is not determined merely by the number of languages one speaks, or the number of countries to which one has travelled. I have many friends who could be considered quite ordinary citizens but who possess an inner nobility; who have never travelled beyond their native place, yet who are genuinely concerned for the peace and prosperity of the world.” SGI Founding President Daisaku Ikeda shared in a lecture at Columbia University, New York, in 1996.

In the same lecture, President Ikeda reminded us that true global citizenship begins with: “The wisdom to perceive the interconnectedness of all life.” To truly live with this wisdom means widening our gaze. It means seeing the sacred in the everyday – the earth beneath our feet, the wind on our face, the food on our table. It means awakening to the truth that our wellbeing is braided into the wellbeing of many others; most of whom we will never meet.

“The courage not to fear or deny difference but to respect and strive to understand people of different cultures and to grow from encounters with them.” This courage isn’t only about crossing borders between nations; it is also about crossing the borders within ourselves. For example, can we bridge the distance between the urban and the rural, not with sympathy but with profound respect and gratitude?

“The compassion to maintain an imaginative empathy that reaches beyond one’s immediate surroundings and extends to those suffering in distant places.” Such compassion is the foundation of human revolution. It allows us to act consciously and consistently, not for applause, but because we have felt another’s burden as our own. It is the spirit of the Bodhisattva: to shoulder the pain of the world, and transform it into hope.

Towards the end of the lecture, President Ikeda shared, “The all-encompassing interrelatedness that forms the core of the Buddhist worldview can provide a basis for the concrete realisation of these qualities of wisdom, courage, and compassion.”

We are not separate islands of existence. We are strands in a vast web of life.

And in the words of Henry David Thoreau: “Not till we are lost, in other words, not till we have lost the world, do we begin to find ourselves, and realize where we are and the infinite extent of our relations.”

Let us not wait to lose the world to finally see it. Let us live wide awake to the ones who secretly sustain us and begin, in earnest, to sustain them in return.

Restoring Dignity, One Brick at a Time Gunjan Mathur | Women’s Division | Delhi

Growing up, I struggled with academics. I didn’t have strong grades, nor a clear vision for my future. Surrounded by intellectuals, I often felt invisible, unworthy, and small. But in 2004, my life began to shift when I became a voluntary member of Bharat Soka Gakkai (BSG).

Through BSG, I encountered my mentor, Dr. Daisaku Ikeda, whose writings completely changed my view of life and leadership. I was especially moved by his words: “The most important requisite for the educated is to know the thoughts and feelings of the marginalized.” His guidance sparked a new way of thinking in me – education wasn’t just about degrees. It was about becoming a person who uplifts others.

Motivated by this philosophy, I moved from a simple B.A. in Programming to a postgraduate degree in Conflict Transformation and Peacebuilding at Lady Shri Ram College, Delhi University. While studying inter-religious conflicts in rural India, I came across something that wasn’t in any textbook – the silent crisis of sanitation. I saw the absence of toilets, the lack of menstrual health infrastructure, and how hygiene was treated as taboo, not policy. I realized that these “conflicts of avoidance” – the ones no one talks about – were just as urgent.

During my internship with UNICEF, I saw it all up close – people with disabilities crawling to toilets, women hiding in shame, communities abandoned by policy. In meetings filled with jargon, I still felt small – but I held on to the voice of my mentor and the training I had received through my Gakkai activities.

That quiet determination led me to the WASH sector – Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene – a field that in 2011 had little visibility, funding, or respect. When I told people I wanted to work on menstrual hygiene, I was met with puzzled looks. But I couldn’t unsee what I had seen.

Despite rejections, I kept writing proposals. Eventually, I designed successful programs to educate girls in states like Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, conducted workshops, and trained adolescent boys and girls. I led open defecation-free campaigns and created spaces for voices that had long been silenced.

I often go back to the famous anecdote of the three men laying bricks. When asked what they were doing, one said, “I’m laying bricks,” the other said, “I’m building a wall.” But the third said, “I’m building a cathedral.” Though all three seemed to be doing the same task, the third worked with grand and inspiring vision, to which I relate the most. I wasn’t just working on sanitation – I was building dignity.

In 2014, sanitation became a national mission. The issue that no one wanted to talk about suddenly received funding and focus. It felt like the silent work we had been doing in the background was finally being acknowledged. Then, in 2016, WASH was formally recognized as a global priority when it was included as a key target under the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals – especially under SDG 6: Clean Water and Sanitation. What was once overlooked had now found its rightful place on both national and global agendas.

Inspired by my mentor, I also wrote down a 50-year vision. One of my goals was to see an open defecation-free India. We’re not there yet, but change has begun. I’ve seen rural children use toilets for the first time. I’ve seen women reclaim space and dignity. I’ve worked with central government programs, helping shape policy at a national level.

Today, I work at the intersection of policy and practice. I know the sector is full of contradictions – tight budgets, shifting priorities, and high risks. But I’ve also seen how deeply people care. I’ve met young professionals from Ivy League colleges choosing to work in public health and sanitation. That, to me, is real success.

I’ve never won an award or made headlines. But I exist. And that matters. I’m one part of a vast, collective effort to create a healthier, more equitable India.

Dr. Ikeda once said, “For what purpose should one cultivate wisdom? May you always ask yourself this question!” That’s my anchor. No matter where life takes me next, I will keep returning to my “why.” I will continue to serve, uplift, and build. One brick, one person, one act of courage at a time.

Where Architecture Meets Empathy Yoko Rao | Young Women’s Division | Noida

I’m an architect by profession and was introduced to the world of Soka Gakkai right from birth, with both my parents being practicing BSG members since before.

Growing up surrounded by the writings and guidance of Dr. Daisaku Ikeda, I took him on as my lifelong mentor. His peace proposals, especially those on human rights and sustainability, left a deep impact on me. I often asked myself: How can I contribute to society as an architect? I didn’t have the answers back then, but one thing was clear – I wanted to live true to my mentor’s vision.

As I pursued my studies, my desire to build a safer, more inclusive India grew stronger – especially for women and children. I learned that something as basic as the lack of toilets had far-reaching consequences. Women in rural areas are more vulnerable to sexual assault due to open defecation. They also face severe health risks due to poor sanitation. This drew me to SDG 6 – Clean Water and Sanitation – and made me determined to contribute meaningfully to the WASH (Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene) sector.

Wanting to gain hands-on grassroots exposure, I applied to a prestigious fellowship program that allowed me to work on a real-world project with an NGO. That’s how I landed in a small village near Madurai, Tamil Nadu, called Silaiman. My project spans across three nearby villages – Keeladi, Konthagai, and Panayur – where I’ve spent the past six months designing and constructing sustainable, inclusive, cost-effective toilets for under-resourced households.

Working at the grassroots completely changed my perspective. I learned that every community has its own rhythms, reasons, and logic. You can’t just enter with solutions crafted in an air-conditioned office and expect change. The community must be part of the solution for it to truly last.

I realized that the core issue wasn’t just the lack of toilets – it was the mindset. Many villagers see toilets as something the government or an NGO should build, not something they can or should take ownership of.

To shift this, we introduced a revolving fund system. We provide interest-free loans to households, with part of the cost contributed by the family. This creates ownership and pride in the process. Families co-design the toilet with us, so they understand the construction process and can replicate it independently in the future – even if a professional isn’t around.

Once the loan is repaid, that amount is passed on to the next family – allowing the same funds to benefit more households over time. This simple model reduces dependency on external funding and empowers the community to build sustainably from within. If successful, the NGO plans to scale this model to other regions too.

This work is a small but significant step toward the promise I’ve made to my mentor. More than just a fellowship project, this has been a turning point in my life. I now clearly see why I chose architecture – not just to build structures, but to build dignity, health, and opportunity.

This journey has taught me that true design isn’t just aesthetic – it’s empathetic. And change doesn’t begin with grand plans – it begins with people.

With this renewed determination, I am committed to continuing my work in the WASH sector even after the fellowship ends. I’m more confident than ever in my mission: to use architecture as a tool for human transformation. And with my mentor’s guidance in my heart, I will keep building – not just toilets, but hope, one household at a time.

SDG Tip for Daily Life

SDG Tip for Daily Life

Support Rural Craftsmanship

Rural India sustains not just food systems, but also rich crafts and traditions. Try switching to handwoven fabrics, earthenware, or locally made utensils. These often come from the same communities that grow our food.

Updates

BSG has now Successfully Held over 241 SOHA Exhibitions

The ‘Seeds of Hope and Action (SOHA): Making the SDGs a Reality’ exhibition has travelled to 210 destinations across the country, including: Chandigarh, Amritsar, Jaipur, Delhi, Karaikal, Gangtok, Kalimpong and Hurda, Rajasthan.

Read more

BSG forms the 36th SDG Club in Bhaskaracharya College of Applied Sciences, Delhi University

As part of its mission to foster young SDG ambassadors in Indian schools and colleges, BSG established the36th SDG Club in Bhaskaracharya College of Applied Sciences, Delhi University.

Read moreContact Us

Any queries or suggestions regarding the newsletter can be addressed to sdg@bharatsokagakkai.org

Any queries or suggestions regarding the newsletter can be addressed to sdg@bharatsokagakkai.org

To know more about the ‘BSG for SDG’ initiative, visit the BSG for SDG website

To know more about the ‘BSG for SDG’ initiative, visit the BSG for SDG website

Download the ‘BSG for SDG’ mobile app with the carbon footprint calculator

Download the ‘BSG for SDG’ mobile app with the carbon footprint calculator